Remember the days when Internet Explorer was the stubborn elder of the browser family, and Firefox was the rebellious teenager? Well, enter Google Chrome, the prodigious youngster that outsmarted its siblings and practically sent some to the retirement home.

Why, you ask? How did Chrome climb to the summit of the browser world, towering above its predecessors and competitors? The answer isn’t as simple as, “Oh, it’s made by Google.” No, siree! (Let’s be honest, that name carries some weight). Chrome’s meteoric rise is a blend of innovation, perfect timing, and perhaps a sprinkle of that ol’ Google magic.

While many browsers were wrestling with speed and compatibility issues, Chrome entered the scene with a cool head, offering a sleek design, impressive speed, and a promise of a continually evolving ecosystem. And guess what? They delivered. Chrome was like that new kid in school with snazzy sneakers, who, surprise, surprise, also turned out to be the class valedictorian.

But, of course, this is just the glossy cover of a very intricate story. Dive in, and let’s unravel the saga of how Chrome evolved from a mere gleam in Google’s eye to the reigning monarch of the browser realm. How did Chrome emerge as the unequivocal champion in a sea of alternatives? Time to dive deep into this digital journey. Are you ready? Because Chrome certainly was!

The Internet before Chrome: The first browser war

Take a moment and cast your mind back. Before the age of Chrome, the internet was a vastly different landscape. Dial-up tones, chat rooms, and a time when “surfing the web” was an adventure – partly exciting and exasperating.

Enter the scene, Internet Explorer (IE). This browser was like the unavoidable guest at every party – omnipresent and somewhat, well, imposing. IE was bundled with Windows operating systems and had the home-field advantage. It was the Colossus of browsers, and while it might not have been the most efficient or loved, it surely dominated. And for many, that was the window to the Internet.

But the internet is all about constant competition, right? Especially on its dawn. And that’s where Netscape comes into the picture. This browser, with its charismatic Navigator mascot, was trying to cut IE’s party short. Navigator was revolutionary for its time, bringing in features and interface designs that would lay down the foundational concepts for future browsers. And while it did give IE a run for its money, corporate battles, and a few strategic missteps (thanks in part to the relentless pressure from Microsoft) saw its eventual decline.

Back in the 90s, when the internet was still in its punk rock phase, a rebel Netscape entered the scene, causing quite the stir. 1994, the year grunge music was on full blast, “Friends” had just premiered, and Netscape decided to join the party.

What made Netscape truly special was its audacity. At a time when the internet was the Wild West, and digital pioneers were scrambling to find a way to navigate it, Netscape provided a sleek, user-friendly interface (as for that time). It was a digital compass, guiding users through the untamed expanses of the web. And the cherry on top? It was free for non-commercial users.

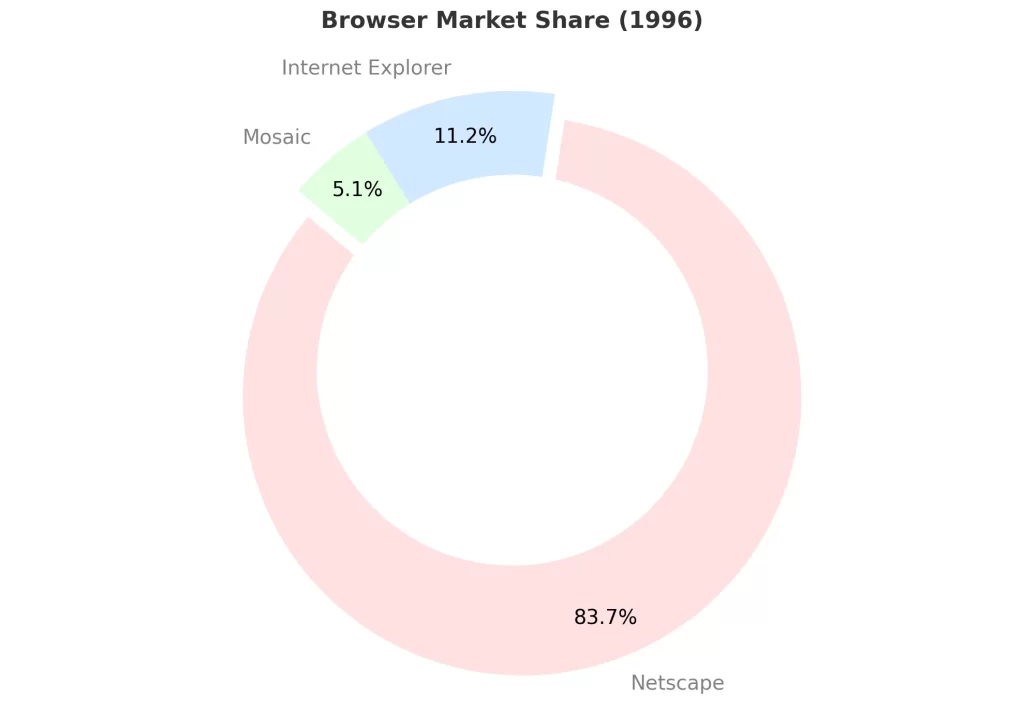

By 1996, this feisty upstart, against all odds, was the kingpin of the browser realm, claiming a whopping 82% of the market share. The reasons were clear: it was innovative, speedy for its time, and offered features that made web navigation seem less like a chore and more delightful. It was like the digital equivalent of discovering the coolest club in town before everyone else did.

However, every epic saga has its titanic clashes. Enter the “First Browser War.” The underdog, Netscape, faced off against the tech titan, Microsoft’s Internet Explorer (IE). While Netscape basked in its glory, Microsoft was strategizing, plotting, and prepping its battle plan.

The first major salvo came in the form of Internet Explorer 4. In a move Sun Tzu would envy, Microsoft decided to bundle IE4 with Windows. For the average user, this was convenience personified. Why download another browser when you’ve got one embedded right into your operating system? This strategic move tilted the scales in favor of IE. It was like giving Usain Bolt a head start in a 100-meter race.

For all its early dominance, Netscape faced an existential threat. Microsoft’s aggressive push and deep pockets, and integration capabilities began chipping away at Netscape’s user base. What was once a massive 82% stronghold started dwindling.

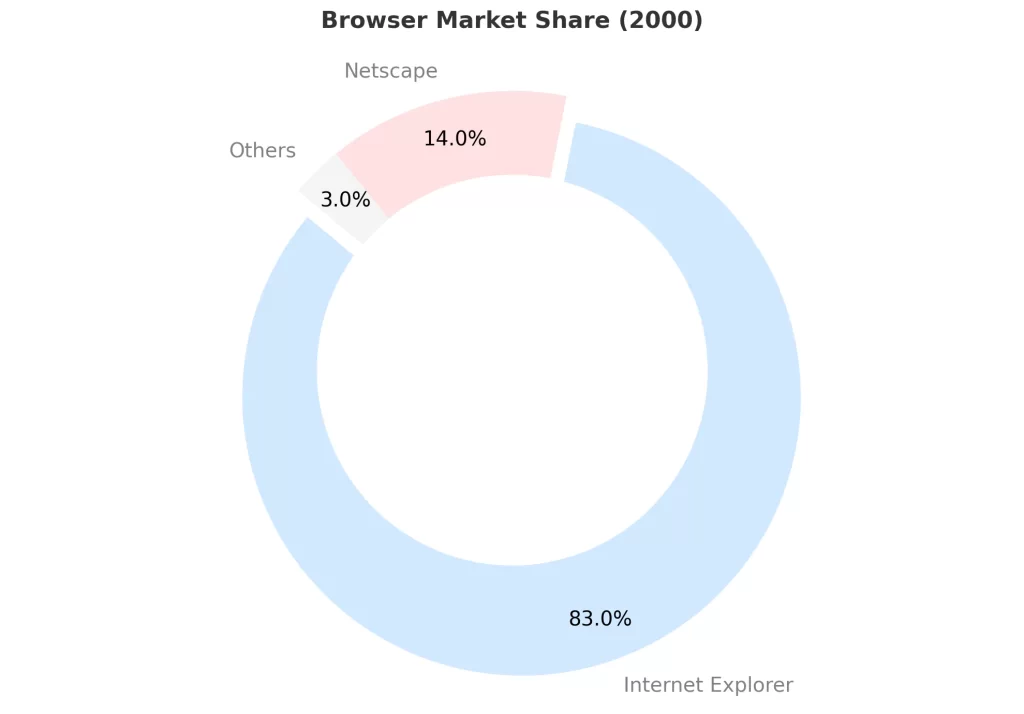

By the new millennium, IE took 83% of the market share, with only 14% left for Netscape. And that was the time when Microsoft won the First Browser War. They’ve found a simple solution: simply adding their browser to their OS. Taking into account the speed of Internet connection, who could beat them? The Internet wasn’t fast enough to let you download Netscape with just one click and a couple of seconds. And that was the field where no one could defeat Microsoft, at least for that time.

The crux of the First Browser War wasn’t just about market shares or technical prowess. It was emblematic of the seismic shifts happening in the digital realm. It was about control, influence, and shaping the very fabric of the nascent internet. With its early innovations, Netscape had thrown down the gauntlet, but with its immense resources and strategic acumen, Microsoft was more than prepared to pick it up.

The Internet before Chrome: The second browser war

By the dawn of the new millennium, the digital coliseum had seen its first major clash. Internet Explorer (IE) stood tall, almost invincible, with a staggering 92% market share by 2002. Netscape, the previous IE competitor, was acquired in 1998 by AOL for $4.8 billion, but that was a new one to come – Firefox.

2002 was significant not just for IE’s dominance but also because it was the year Mozilla Firefox was launched. The Mozilla Foundation worked diligently to craft a browser that was everything IE was not: faster, more secure, and inherently customizable. In essence, Firefox was born out of the frustrations and limitations of IE.

And then began the Second Browser War. Unlike its predecessor, this wasn’t just a tussle for market shares; it was a battle for the soul of the Internet. Firefox represented a movement that challenged the status quo, urging users to question why they were settling for a lackluster browsing experience. Why endure a slow, often crash-prone browser just because it came pre-installed?

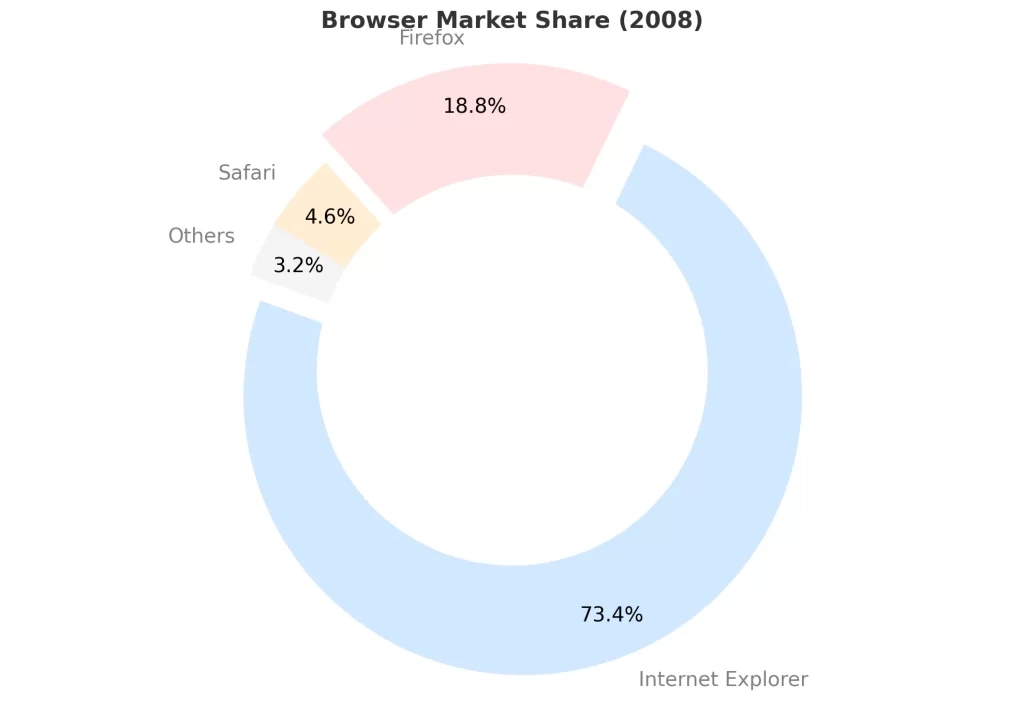

Firefox’s rise highlighted IE’s glaring inadequacies. It wasn’t just about superiority in speed or functionality but also about the fundamental question, “How do we browse the Web?” Firefox became a stark contrast to the corporate behemoth that was IE. And the market responded. Firefox steadily chipped away at IE’s dominance, reaching a commendable 19% market share in 2008. Not enough to overthrow the reigning champion, but enough to make it sweat.

A crucial game-changer in this war was the advent of high-speed internet. Previously, downloading a new browser was a task only for the patient or the brave. But with faster connections, switching to a superior browsing experience was just a few clicks away. This seemingly minor shift in internet infrastructure played a pivotal role in leveling the playing field. It allowed Firefox to present itself as a viable alternative and encouraged users to break free from the inertia of sticking with the default.

While Microsoft did eventually retain its crown in the Second Browser War, Firefox’s challenge marked a significant turning point. It highlighted that dominance wasn’t just about sheer numbers but about meeting users’ evolving needs.

The Chrome time comes

In the early 2000s, Google was more of a David than today’s Goliath. Microsoft had a stranglehold on the internet with its Internet Explorer browser, which was installed on a staggering 90% of all computers. This dominance meant that Microsoft essentially controlled how most people accessed Google’s search engine. Just imagine the company that was number one all over the Internet, the gateway to the Internet even, was depending on other Big Tech company and its browser.

To ensure the prospective future, Google had to think on its feet. Their first solution was the Google Toolbar, a browser extension that placed a Google search bar right under the browser’s address bar. This move was a masterstroke, ensuring that hundreds of millions could access Google without relying on Microsoft’s goodwill. But as Google expanded its suite of products, including Gmail, Docs, and Calendar, the company realized it couldn’t forever be at the mercy of competitors. The answer? Own browser.

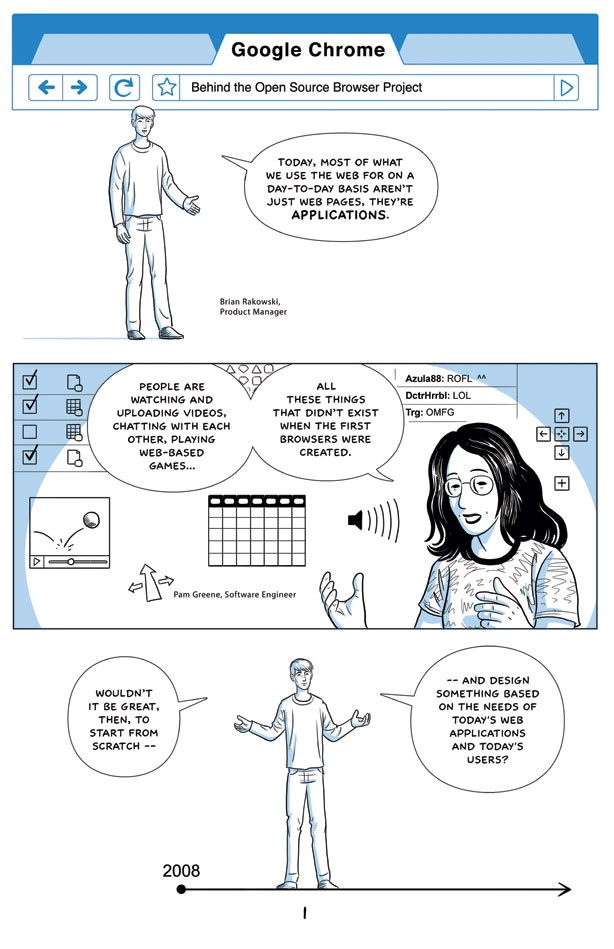

What’s more, while Google was busily expanding its horizons beyond mere search, launching a medley of services, they hit a roadblock. Many old browsers just couldn’t keep up. They lacked the tech finesse to support the innovative features of services like Google Maps. It wasn’t just about delivering search results anymore; Google was sculpting a more interactive, dynamic web. But without the right browser tech, that was simply not possible, at least at the full. And that was one more answer to the question, “Do we need our own browser?”

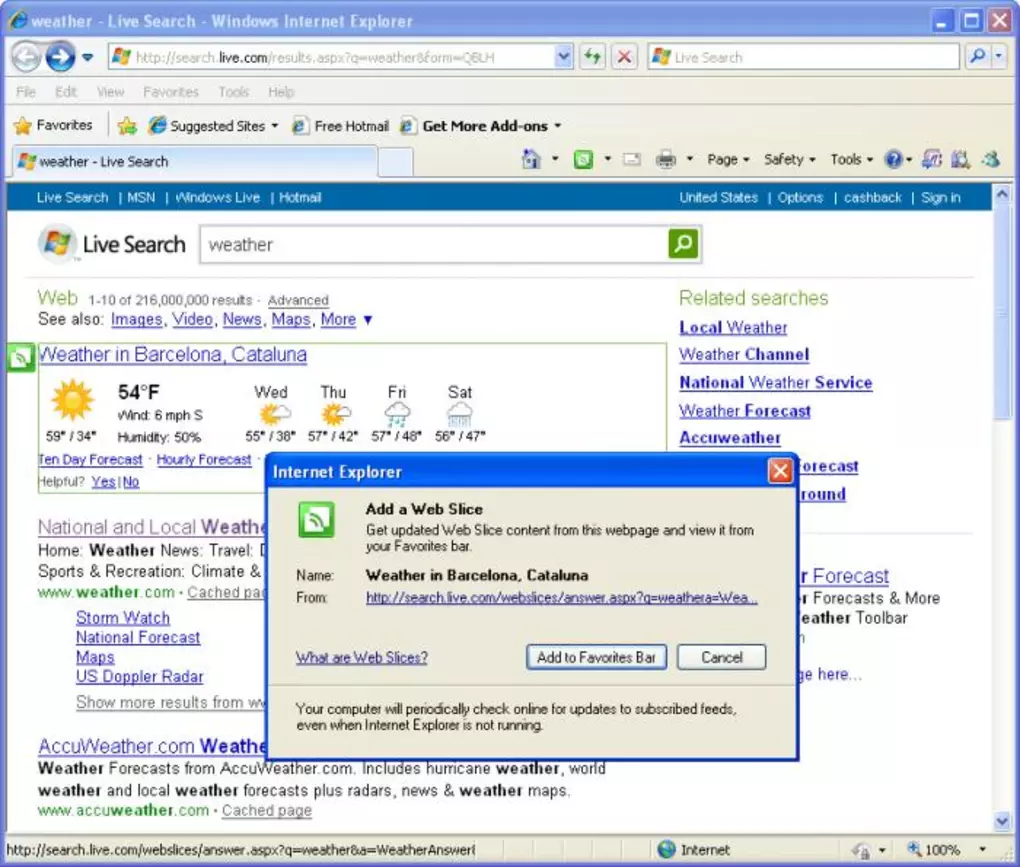

Internet Explorer was like that old, trusty car that everyone had but secretly wished to replace. Sure, Microsoft tried to give it a fresh coat of paint and tweak the engine a bit, but let’s be real: it was the same from 2000. The interface? Cluttered with buttons. Speed? More like a leisurely stroll than a sprint. Usability? Let’s just say it wasn’t winning any design awards.

Just look at this. That’s how the Internet looked like in 2008. Almost 15% of your screen is taken by endless bars: address bar, search bar, toolbar, bookmarks bar, tabs bar, and options bar.

Looks like something you would be never happy with.

Google saw the gaping hole in the market, a yearning for something fresh, efficient, and user-friendly. But the stakes were sky-high. Google couldn’t afford a misstep. A subpar browser would tarnish their reputation, making their entry into the browser market a short-lived experiment. They needed to hit a home run on their first swing.

The good way was the way to the basics. At least when it comes to the interface. They realized that in the race to add features, many browsers had lost sight of what users truly wanted: simplicity, speed, and stability. Google Chrome was more like that. Its architecture was streamlined, ensuring rapid page loads. The interface was clean and intuitive, a great controversy from what you can see above.

But Google’s pièce de résistance was its solution to a problem that had plagued users for years: browser crashes. We’ve all been there, right? You’re browsing, and bam! That’s a crash; you’re here to open everything from scratch. Google addressed this by sandboxing tabs, ensuring that a crash in one tab wouldn’t bring down the entire browser. At least not as frequent as with IE. You can see this approach even now in your Task Manager. Chrome has not one process but a separate one for every tab. And if the worst did happen? A quick restore brought back all your tabs.

***

But when we’re talking about Google Chrome now, we shouldn’t forget it wasn’t just an unexpected plot twist; it was the culmination of a series of moves that spanned nearly a decade. Google Chrome was released in 2008, but there were 3 years of direct development and almost 6 years of indirect efforts.

But the blueprint for Chrome extended beyond just software compatibility. Google’s corporate ledger during this period was awash with strategic acquisitions. That wasn’t tech giants, but usually quite a small companies, but each one was a piece of the jigsaw, securing crucial technology stacks and intellectual properties that would be instrumental.

You can read a great story about the Google Chrome technology stack here.

The Chrome team was formed in 2005 with Ben Goodger; he was a veteran in web browsing, the former lead developer of Firefox, and one of the former Netscape staff members. He was put in charge of choosing a crew as well and have made a choice to hire Firefox contributors, including Darin Fisher, a specialist in network libraries and permissions (including WebKit embedding); Pam Greene, who specializes in layout tests; and Brian Ryner, who was one to add a mouse-wheel option to Firefox.

Isolated tabs

One of the standout features of Chrome became its sandboxing technology, acquired from GreenBorder, which ensured that a crash in one tab wouldn’t bring down the entire browser. This was revolutionary at the time and addressed a major pain point for users.

GreenBorder’s technology functioned as a protective barrier: when accessing a website, it generated a distinct virtual environment, or “sandbox,” exclusively for that session. This ensured that any activity inside one session would be unable to affect other tabs or the overall operating system. By integrating this technology, Google Chrome became more secure, but what’s more important, it became much more stable, and the crashes of the entire browser became less frequent.

And one more thing – it made the overall browsing experience faster, as each tab ran separately.

V8 Engine

Developed by Ian Back and others, V8 Engine gave a lot to Chrome’s performance. This engine was specifically designed for recursive JavaScript tasks, ensuring web applications ran smoothly. V8 was multi-threaded, making the most of multi-core processors, and it could even predict how you might use your JavaScript code, optimizing it on the fly.

V8 became Google’s open-source JavaScript and WebAssembly engine, meticulously crafted in C++. It’s the powerhouse behind Google Chrome. But its influence doesn’t stop at the browser; it’s also the engine that fuels Node.js, a popular server-side runtime environment.

At its core, V8 is designed to be fast and efficient. It first generates an abstract syntax tree, which is then transformed into bytecode using the internal V8 bytecode format. This bytecode is then compiled into machine code using just-in-time (JIT) compilation, ensuring rapid execution. This approach is a departure from the traditional interpretation of JavaScript, allowing for much more performant execution, especially for extensive applications.

Gears integration

Google Chrome integrated the Gears to augment its JavaScript prowess. With every Chrome installation, Gears seamlessly comes onboard, elevating the browser’s functionalities at a pace previously uncharted by traditional plugins. Among its arsenal are enhanced local cache structures, databases for local storage, sophisticated location data handling, robust background tasks, and comprehensive file management. The inclusion of Gears not only empowers web developers with a broader canvas but also elevates applications, including Google’s flagship services like Google Maps and Google Docs.

The iteration of Gears in 2008 in Chrome mirrors functionalities found in the V8 engine and the SQLite code. That made a Chrome team a path to experiment with HTML5; now, that’s the industry standard, but a flashback to 2008 was just a concept.

Chromium Projects

When I was young, I wondered what the Chromium is. But here’s an answer, in September 2008, Google open-sourced its efforts behind Chrome, launching the Chromium Projects.

This made it possible to make Chrome more open and attract third-party developers, effectively following the same path that Mozilla took with Firefox. This was in stark contrast to Microsoft and their closed-source Internet Explorer.

The launch of Google Chrome was also a creative one. They dropped an app and designed a comic book to present their new browser.

You can read the full comics here. To swipe pages, simply click on them.

Chrome’s launch

That was September 2, 2008, when Chrome was launched. Here’s how it looks like:

No search bar; it’s merged with the address bar, most visited tabs, and clean interface. And a way to download and install a browser with a couple of clicks on the Google website. In the first year, Chrome’s market share was less than 1%, but users liked it. So that was only the question of time when it would become a king.

Microsoft probably realized the threat, but the Internet Explorer architecture was a problem. That was not only about changes to the interface or something like that. To compete with Chrome, Microsoft needed an absolutely new browser. And it seems they haven’t realized the threat or simply decided this thing is unimportant. But the fact is, Microsoft launched their web browser, Microsoft Edge, based on Chromium only in 2015; that would be too late for that time.

***

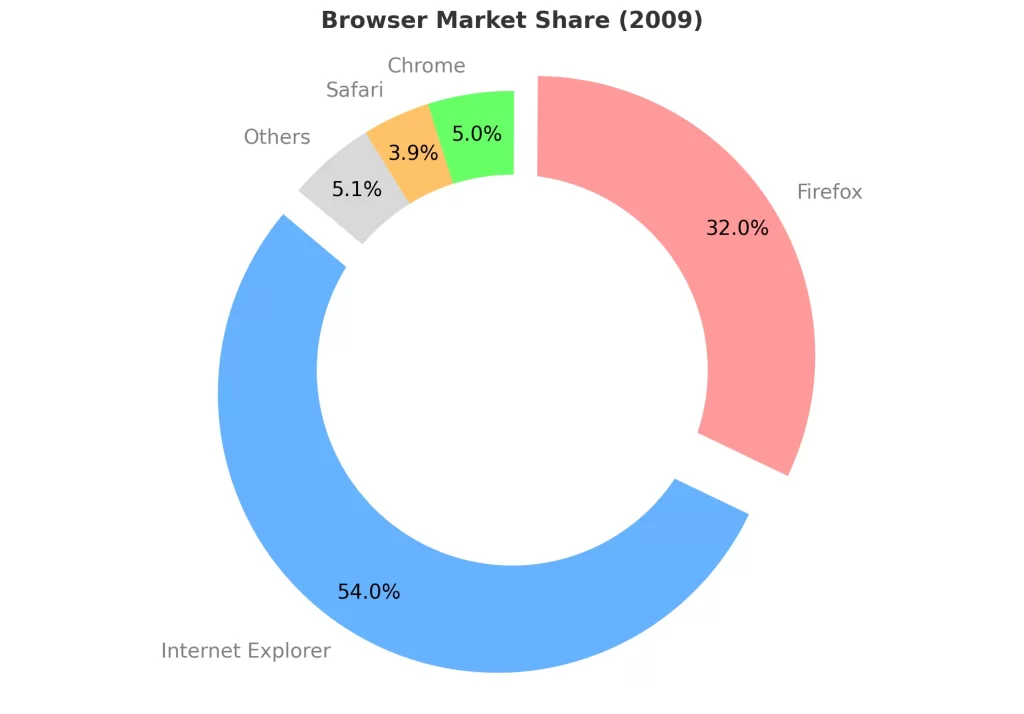

By the end of 2009, Internet Explorer was rapidly losing popularity, retaining about 54% of the market share. Firefox was rapidly catching up with almost 32% of the market share. Chrome made striking progress during this time, reaching a market share of 5%. Seems small, but it was only a year since Chrome’s launch.

And most importantly, there was a trend, Chrome was growing 20-25% every month, and users loved that it was fast. I would even say very fast. I remember trying Chrome for the first time in 2009 and being impressed by its speed.

Google Chrome Extensions

When one reflects upon the early days of Google’s Chrome, one aspect that stands out prominently is its pioneering role in championing browser extensions. Today, extensions may seem as commonplace as the air we breathe online. However, in 2009, they marked the dawn of a new era, setting the stage for an expansive digital revolution. What’s the point of trying to add all the functions people may need right inside the browser? The better way to keep it simple and fast but let people install what they need. So was the idea behind the Chrome extensions.

In December 2009, Google audaciously unveiled its extensions gallery, offering users a panoramic view into a world of third-party plugins. This wasn’t merely about additional features; it epitomized the essence of customization, enabling users to mold Chrome into a tool tailored specifically to their needs. Through this, Chrome wasn’t just a browser; it metamorphosed into a dynamic platform replete with limitless possibilities.

To put the groundbreaking nature of this concept into perspective, by 2009 standards, it was akin to unveiling a new dimension in the realm of browser functionality. Besides its celebrated sandboxed tabs, extensions swiftly became the cornerstone of Chrome’s identity. Their popularity? Nothing short of meteoric. Consider this: A mere 12 months post the launch of the extensions gallery, users had a staggering array of over 8,500 extensions and 1,500 themes at their fingertips. An even more telling metric: Roughly a third of Chrome’s vast 120 million-strong user base had jumped on the extensions bandwagon. The cumulative tally? An impressive 70 million extensions and themes gracing Chrome browsers worldwide.

This wasn’t just about numbers, though. It was emblematic of a shift in user behavior and expectations. With extensions, users weren’t passive consumers; they became active participants, selecting, curating, and refining their online experiences.

But with extensions, Google faced a lot of security issues. That’s why Google has banned the installation of the extension not from the Web Store and announced a lot of security measures: in 2013, multi-purpose extensions were banned; in 2014, Google made Web Store the only way to install the Chrome extensions; in 2016, they released new security guidelines and in 2019 they announced the new security measures.

The growth and the domination

Tracing back to May 2012, a critical juncture occurred in the browser wars: Chrome surpassed the erstwhile giant Internet Explorer. This wasn’t merely a change in rankings; it symbolized a changing of the guard. If the early 2000s marked the reign of Internet Explorer as the torchbearer of the nascent internet, by the early 2010s, a new monarch was being coronated.

As 2014 dawned, Google Chrome stood on the precipice of digital dominance. A staggering growth rate had seen its market share balloon by 155% in a half-decade, capturing the loyalty of over 310 million netizens. But this was merely the prologue.

The initial salvo of the year was fired in January: the unveiling of Chrome for Android and iOS. This might seem like a minor ripple in the broader arc of Google’s innovations, yet its significance was profound. That was a time of the rise of everything mobile; smartphones finally became not add-ons for personal computers, and users were increasingly migrating. And now Google wasn’t an underdog; the company was in the front of a trend.

Google has made one more move, giving ways to monetize extensions and expanding the paths of how developers could monetize their content. Why that’s important? Because without proper monetization, there’s always a chance the extensions tab will be forever dedicated to things created by coders who have a lot of free time and less work.

And a company gave way for big players to monetize with their extensions. That meant that a lot of companies and teams would be offering their products, making money, and… enhance Chrome.

In March 2014, Google’s decision to retool its monetization strategies offered a beacon. Developers could previously monetize their offerings in several ways: free trials, one-off payments, subscriptions, and in-app payments. But the update flung open the doors to extension developers specifically, granting them unprecedented access to all these avenues. Although this might’ve felt inconspicuous to the market then, it was an unequivocal nod from Google towards its commitment to fortify the third-party ecosystem of Chrome.

That was a turning point in building a Chrome ecosystem when you’re not just using your browser to get access to web pages (and therefore, you’re easy in switching to any other); no, your browser is the operating system inside the operating system (rhetorically, of course). How can I switch from Chrome if I have so many extensions installed? Even if I download any other browser, Opera, for example, I simply will need to start from scratch.

Once considered a pet project of solitary developers, extensions transitioned into heavyweight contenders in the digital arena: for some companies, like Microsoft, they turned into a way to promote their products; for others, a way to build a business. For some companies, Chrome extensions even become the main part of their business.

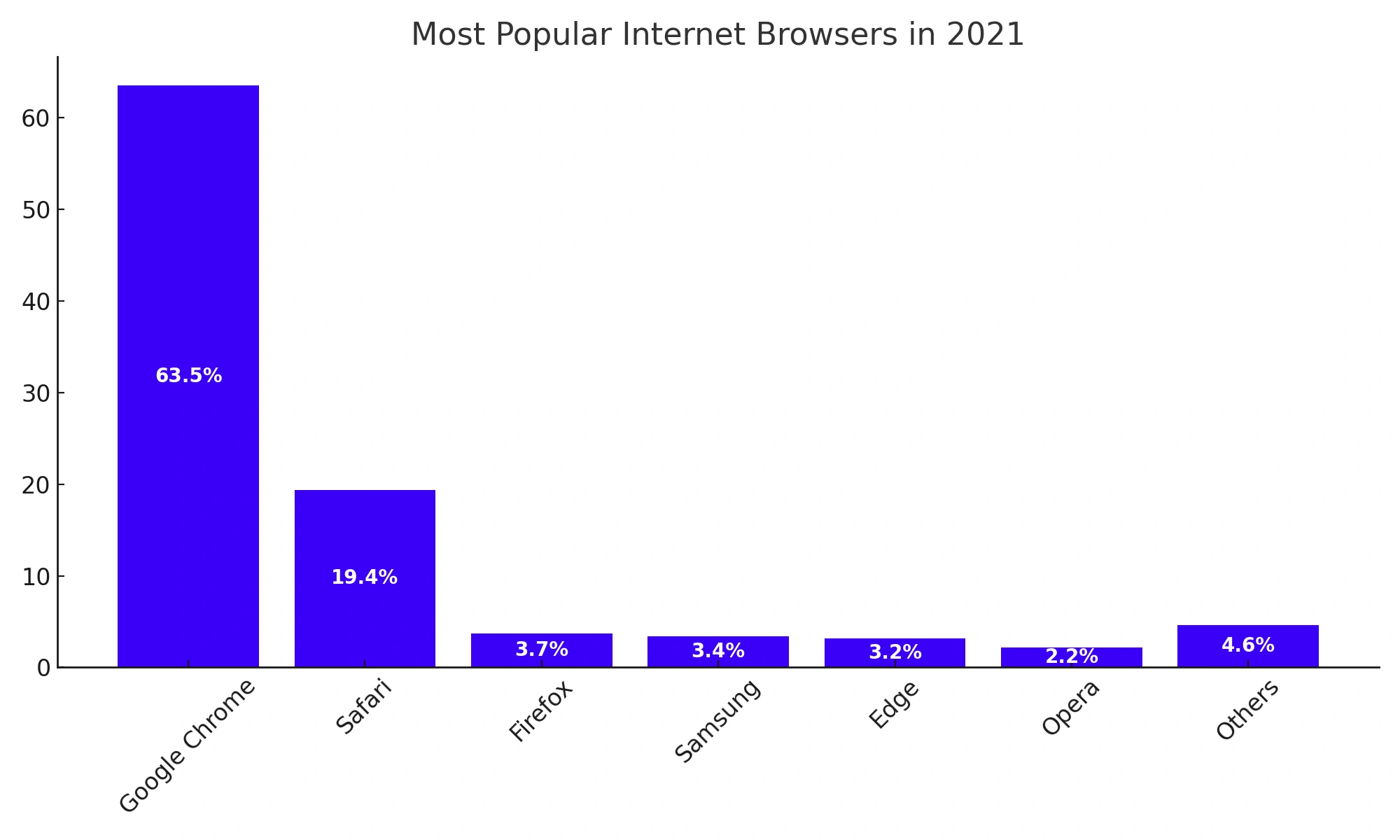

Zooming out to a broader timeframe, by 2021, Chrome’s dominion over the browser landscape became increasingly evident. Holding a commanding 65% market share, it overshadowed its closest competitor, Safari, which managed to secure 19.4%. These figures aren’t just about market dynamics; they’re a testament to user preferences, trust, and the overarching influence of Google’s ecosystem.

So, what propelled Chrome to such an illustrious position? While its innovative features, like the aforementioned extensions, played a pivotal role, Chrome also benefited from Google’s integrated ecosystem. Synced bookmarks, passwords, and seamless transitions between devices made it more than just a browser; it became a holistic digital experience.

Fast forward to 2022, and Chrome’s hegemony shows no signs of waning. With a staggering 3.2 billion users globally, this isn’t just dominance. These numbers don’t merely represent a ‘user base’; that’s how the Internet looks like.

So why has Microsoft lost?

The perspective goes far deeper than just the surface-level browser wars. Indeed, the contention isn’t merely about browser functionality or market share but rather a reflection of two differing strategic vantage points and corporate priorities.

It’s a fundamental truth: not all battles are of equal importance for every contender. For Microsoft, a behemoth with its fingers in numerous technological pies, browsers may not have been the paramount front. This isn’t to imply a lack of foresight but rather an insight into their broader strategy. Historically, Microsoft’s core strength lay in its operating systems and enterprise solutions, domains where they were undisputed leaders. The browser? Arguably a secondary front in the grand scheme of their expansive portfolio.

Google, on the other hand, had a different trajectory. Their core business inherently emphasized the browser’s importance as the gateway to the Internet. For Google, Chrome wasn’t just another product; it was the digital conduit through which they could further their business.

To say Microsoft underestimated Google may be an oversimplification. Instead, it might be more accurate to suggest that the priority and strategic importance assigned to the browser domain differed between the two tech giants. Google’s raison d’être was intrinsically linked to the internet and its accessibility, making Chrome a critical piece in their puzzle. In contrast, while Microsoft surely recognized the internet’s importance, their expansive portfolio meant they had to allocate resources and focus across multiple fronts, perhaps diluting their emphasis on the browser.

But let’s also entertain a critical perspective: Did Microsoft genuinely neglect the browser domain? Or was it a calculated decision based on their understanding of their core competencies and strategic imperatives? With their vast resources and technological prowess, there’s little doubt that had they thrown their full weight behind the browser war; the narrative might have been different.

The browser’s story isn’t just about technology or market share; it’s a tapestry woven with threads of strategy, corporate vision, and the ever-changing digital landscape. While Google has etched its mark as the browser vanguard for this digital age, one can’t help but ponder the “what ifs” had Microsoft chosen to prioritize this domain with the intensity and focus it merited.